|

| Scanned catalogue page for a 1939 Schwinn Paramount, courtesy of bulgier.net. This bike had a single speed and was designed for 6 day bicycle races. |

In my blog post "Bicycling History Seen from the Tour", I discussed the winning bicycles of the Tour de France from 1910 to the present to shed light on the history of bicycle technology. At the end of that post, I promised to look at the history of some consumer grade bicycles to get a different view on that history. Since then, I came across an excellent collection of Trek catalogues that will facilitate that look. However, Trek first started manufacturing in 1978, and I thought it would be interesting to look at some history before that. The only comprehensive set of catalogues I found for the 1950s and 1960s were for Schwinn bicycles, interesting in their own right but perhaps a somewhat skewed view on road bikes. That said, Schwinn history, supplemented with other historical tidbits, is the topic of this post.

Resources

- My Page on Bicycle Anatomy: This post is one where knowledge of bicycle anatomy is important. I am working on a page for this blog to serve as a reference on bicycle anatomy. This page is not yet complete, but I have published it in its incomplete form to help readers with this post.

- Tom Findley has assembled the amazing collection of Schwinn catalogues which were the inspiration for this post.

- The Schwinn Bike Forum offers the "Schwinn Lightweight Data Book" containing more detailed specifications than the above for the years 1960 through 1979, the years in which I happen to be most interested.

- The article "Chicago Schwinns" by Sheldon Brown and the links therein to articles on the Schwinn Varsity, and fillet-brazed Schwinns present a wonderful overview and perspective on the place of Schwinn in road bike evolution.

- Mark and Laurie Bulgier on their deceptively modest looking home page link to an astonishing collection of bicycling information, including old bike catalogues which supplemented the Schwinn data but much more importantly has a wealth of information on older European bikes.

- "Disraeli Gears" is a site devoted to derailleurs. This site proved remarkably helpful in illuminating otherwise dark corners of bicycle history.

Overview

The safety bicycle a.k.a. upright bicycle, a bicycle with two equally-sized wheels, a chain drive to the rear wheel, and pneumatic tires, was introduced at the very end of the 19th Century. The dramatic increase in usability this design engendered launched a bicycle boom. Schwinn Bicycles was founded in 1895 to take advantage of this boom. In the United States, this boom ended almost before it started and was over by 1910. By then, cars had largely replaced bicycles which were relegated to childrens' toys. In contrast, bicycles remained much more popular in Europe, being used by adults for commuting, touring, and racing. Schwinn rolled with this punch and developed a hugely successful business supplying the bicycles that every kid wanted due to their extreme durability, stylishness (they looked like motorcycles), and intensive advertising campaign. However, Schwinn wanted to reinvigorate the adult market for lightweight bicycles and starting in 1938, reintroduced adult bicycles, including their top of the line Schwinn Paramount constructed very much like a European racing bicycle. Although this was a money loosing proposition for Schwinn at first, they successfully developed an adult market in the US which paid off for them in the 1960s and the 1970s.

From when they first reintroduced adult bicycles in 1938, Schwinn offered three quality levels of frame on their lightweight bicycles. The least expensive line used low grade, seamed steel tubing fabricated and welded in the Schwinn factory. This is the same technology Schwinn used in their heavyweight childrens' bicycles. The most expensive line was the Paramount which used very high end, bicycle specific tubing like Reynolds 531 and lugs to construct a traditional high end European-style frame. Perhaps the most interesting were the bicycles in the middle. They used unbranded chrome-molybdenum seamless tubing and the frame was brazed rather than welded, not using lugs, but a process called fillet brazing. Although interesting and perhaps prescient, foreshadowing the TIG welded steel frames of today, this mid-level frame technology went largely unnoticed and did not have much of an impact on bicycle technology. These filet-brazed Schwinn's are highly prized by collectors today, however.

|

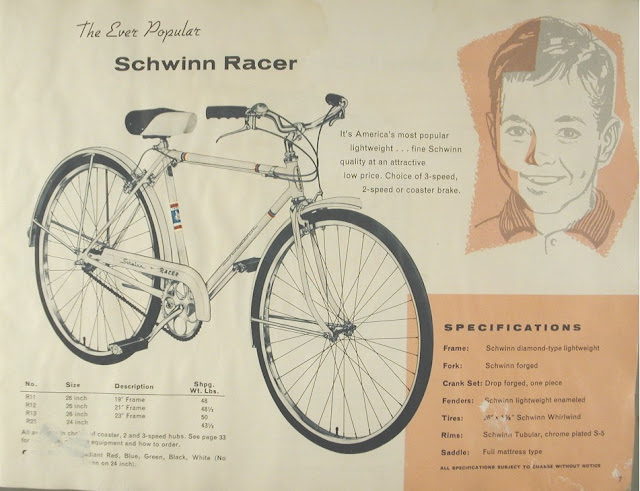

| Scanned Page from the 1961 Schwinn Catalogue courtesy of Tom Findley |

From when they first reintroduced adult bicycles in 1938, Schwinn offered three quality levels of frame on their lightweight bicycles. The least expensive line used low grade, seamed steel tubing fabricated and welded in the Schwinn factory. This is the same technology Schwinn used in their heavyweight childrens' bicycles. The most expensive line was the Paramount which used very high end, bicycle specific tubing like Reynolds 531 and lugs to construct a traditional high end European-style frame. Perhaps the most interesting were the bicycles in the middle. They used unbranded chrome-molybdenum seamless tubing and the frame was brazed rather than welded, not using lugs, but a process called fillet brazing. Although interesting and perhaps prescient, foreshadowing the TIG welded steel frames of today, this mid-level frame technology went largely unnoticed and did not have much of an impact on bicycle technology. These filet-brazed Schwinn's are highly prized by collectors today, however.

Beginning early in the 20th century, bicycles with multiple gears began to appear in Europe, both gears internal to the rear hub (e.g. "three speed hubs") as well as derailleur gears. In the beginning, derailleur gears were largely limited to three gears relatively similar one to another in size, so that derailleur gears did not have a significant advantage over internal hub gears for long distance riding or for racing. A catalogue from the "late 1930s" from the British firm Evans, lists derailleur bicycles with two and three speeds. In 1952, the French firm Pelissier offered a randonneuring bicycle with 8 speeds, 4 sprockets in the back and two in the front, including an astonishingly low alpine gear, and Peugot's top of the line racing bike, the PH10, also offered 8 speeds. The dominant British bicycle manufacturer, Raleigh, offered no derailleur bicycles in their 1951 catalogue; even their top of the line racing bike used a three speed hub, but by 1957 are offering a derailleur-equipped bicycle with 10 speeds. The first year Schwinn sold bicycles with derailleurs was 1960.

Schwinn Derailleur Bike History: 1960 - 1977

|

| 1960 Schwinn Varsity. The lever with the white handle that extends from the front sprockets towards the seat is the front shifter. This photograph courtesy of the Schwinn Bike Forum. |

In 1960, Schwinn introduced two or three derailleur bicycles including an 8 speed Schwinn Varsity for $69.95 and a 10 speed Schwinn Continental for $86.95. I was unable to determine if the 1960 Schwinn Paramount used a derailleur. Some of the most important features of this initial release were as follows:

- Rather than using the Huret Allvit derailleur set that later became standard on the low-end Schwinn road bikes, these bikes used the Simplex Tour de France derailleur set. The most striking difference between this derailleur set and what I became to think of as the "standard 10 speed" of my youth is that the shift lever for the front derailleur was not in the standard position on the down tube of the frame, but was way down on the derailleur itself. Because of the risk of reaching down that low while riding this position was referred to as a suicide shifter.

- 10 speeds was not yet quite standard. Presumably to differentiate the less expensive Varsity from the more expensive Continental, the Varsity only had 8 speeds (2 in the front and 4 in the back) whereas the Continental had 10 (the "standard" 2 in the front and 5 in the back.) Other features that differentiated these two bikes were that the Varsity had a heavy, flat, forged fork like the rest of the Schwinn line whereas the Continental used a more European or traditional tubular fork, the Continental had quick release hubs whereas the Varsity had wing nuts, and the Continental had center pull brakes whereas the Varsity had side pull brakes.

- Although the Continental had the "standard" 27 x 1¼ inch tires, the Varsity had the same sized tires as the Schwinn 3 speeds, 26 x 1⅜ inch.

The Varsity and the Continental had a number features in common that differentiated them from European bicycles at a similar price point. The first, already mentioned, was frames made from inexpensive, heavy gauge seamed steel. The visibly obvious reflection of this was the absence of lugs on the frame where the frame tubes joined. The second was use of one-piece, heavy forged steel cranks similar to what Schwinn used on their rugged, childrens' bikes, rather than the three-piece cranks of the European bikes. At the high end, European cranks were made of aluminum alloy and were quite light (and beautiful.) At the low end (the Varsity/Continental price points), they were steel, but still much lighter than the Schwinn cranks. Finally, the Schwinns had heavy steel kickstands permanently welded to the frame. European bikes often had no kickstand at all, but if they did it was made from aluminum alloy and bolted to the frame so that it could be removed. This should have been a hint to me back then that the "10-speed standard" that was forming in my head was open to exception.

In mid-1961, the Varsity got 10 speeds, eliminating this deviation from the "standard" of my mind. However, both the Varsity and Continental continued to use the "non-standard" suicide front shifter. That is also the first year for which I could find specifications for a derailleur-equipped Paramount. This bike used the Campagnolo Grand Sport derailleur and thus had the shift levers for both derailleurs in the "standard" down tube position.

In 1962, the first 15 speed bicycles were introduced by Schwinn (3 gears in the front, 5 in the rear), the Super Continental and the Superior. The Superior was also Schwinn's first derailleur bike with the Crome-Molybdenum, filet-brazed frame. I confess that, at the time, I never appreciated or even noticed the significance of these higher end frames. One reason for this is the absence of lugs; these frames looked like the much heavier and less responsive Varsity and Continental frames. Had I appreciated the higher quality of these frames, I might have not been so surprised by the TIG welded steel frames I encountered when I re-entered the market in 2008.

1963 was a paradigmatic year for me and Schwinn for the following reasons:

- The Varsity got 27 x 1¼ inch tires, eliminating this deviation from the "standard".

- The Varsity and Continental got Huret Allvit derailleurs, putting both shift levers on the down tube, eliminating the suicide front shifter, another deviation from the "standard".

- Comparing the specifications from various years, I think this must be the model year of my Continental, my first 10-speed.

|

| A 1963 Schwinn Continental. Photo courtesy of the CycleThru Blog. Notice the two shift levers on the down tube. |

Thus, by 1963, when I first entered the market, the entire Schwinn derailleur bike line fit my myth of the "standard 10 speed". As it happened, so did virtually every other derailleur bicycle being sold in the US. The evolution of bicycle technology ebbs and flows over time and across different parts of the bicycle. Although the number of rear sprockets on bicycles was changing all the way through 1961, purely by chance few changes occurred between 1961, just before I entered the bicycle market, and the late 1970s, shortly after I had left the market for 35 years. A similar pause in other aspects of derailleur technology occurred at the same time. In my lack of experience, I interpreted this pause, which encompassed the entire time I was in the bike market, as a permanent state, so was surprised in 2008 to find that the pause had ended and that bicycles had changed.

To explain the most significant event of 1964, I need to provide some historical context. Today, Schwinn is simply a brand name licensed and used by a variety of manufacturers, there is really no such thing as a Schwinn bicycle, and certainly Schwinn bicycles are not particularly prized. The final bankruptcy that lead to this state of affairs happened in 2001, but the downward spiral had begun by the late 1970s. In contrast, Schwinn completely dominated the US bicycle industry in 1964 and was one of the most important bicycle manufacturers in the world. The big event of 1964 is that Schwinn rebranded the Huret Allvit derailleur to the Schwinn Sprint derailleur; it still was exactly the same derailleur, still manufactured by Huret in France, but now had the honor of having the Schwinn name on its side. According to Disraeli Gears, this "was the definitive sign to the world that derailleurs were ready for the mass market."

The next event, a relatively minor one, didn't happen until 1967 when the shift levers were moved from the down tube on the frame to the stem. This was done to make them easier to reach and thus safer to use. To those of us who were serious riders, this was a downgrade, a "dumbing-down" of the bikes. Importantly, this change was made on all models EXCEPT for the Paramount.

In 1968 the SS Tourer was introduced, a 15 speed with the mid-level chrome-molybdenum filet braised frame. Rather than using the heavy steel one piece crank that previous models in this range used, it featured a 3 piece, alloy crank, making it much more competitive with European bikes.

In 1969, another "dumbing down" occurred. An additional brake lever was added to the hand brakes that could be reached when one had one's hands on the top of the handlebars. Again, this convenience feature was not introduced on the Paramount.

The next event on which I wish to comment occurred in 1973 - introduction of the Schwinn Le Tour and World Voyager. These were the first Schwinn bikes not manufactured in the US. They were Schwinn branded but manufactured under contract by Panasonic in Japan. As the 70's progressed, more and more of Schwinn's bicycles were manufactured in Japan, and more and more began to use Schwinn-branded derailleurs made in Japan by Shimano or Sun Tour rather than in France by Huret. Although both Shimano and Sun Tour started manufacturing derailleurs in the 1950s, it was not until the 1970s that they were widely appreciated outside of Japan. Thus, I would add one more feature to my imaginary "10-speed standard"; most of the important components, at least on the better bicycles, were made in Europe.

Nothing much happened to Schwinn lightweight bicycles between 1973 and 1977, the last year for which I have found catalogues. In 1978 Trek Bicycles was founded, the topic of my next Bicycle History post. As we shall see, Trek starts out with bicycles that pretty closely match my "10-speed standard" with the exception of using Japanese rather than European components but ends up today with fully modern bicycles. By tracking the history of Trek, we will be able to witness the end of the pause in road bike evolution, an evolution that once restarted, lead to the bicycles that so startled me when I re-entered the market in 2008.

For those new to this blog, each week I am posting an update of my training results; see my previous posts for explanations of my aerobic training program, MAF tests, and this graph.

In this latest iteration, there may be a hint that my performance is leveling off. This is far from certain yet, but if true, would not be surprising. Since the beginning of March, I have been completing increasingly long weekly rides to prepare for my 200K (124 mile) brevet on May 18. Last week, I completed the longest ride in this series, 90 miles. The stress of these rides would be expected to interfere with the aerobic training the MAF test measures. In short, I am starting to draw upon the reserves I built up during December, January, and February.

I believe a typo on caption: A 1993 Schwinn Continental. Photo courtesy

ReplyDeleteGreat catch, THANKS!! I have fixed the error.

Delete11/22/16 ,, just picked up a sky blue continental , with 15 speed sprint derailleurs , sprint quick release hubs front and rear , suicide brake lever combo , can't find it mentioned anywhere , also full chrome fork ,

ReplyDeleteany idea ??

Jay,

DeleteI was unable to find your bicycle. That said, I am far from a Schwinn expert, and as I understand it, Schwinn was known for selling variants of their standard bikes, often not in the catalogue, so you may have one of those. I think you have a very cool bike, and should be very happy with it!

Could this be your bike?

Deletehttp://www.trfindley.com/flschwinn_1961_1970/1962dlr_Super_Continental.html